There’s Nothing Natural About Animal Agriculture

"But in the only rational sense, Nature means the sum of all phenomena, together with the causes which produce them; and in this sense, the course of nature is the course of things as they happen to be, not as they ought to be.”

- John Stuart Mill, 'Nature'

Hearing of processed alternatives or lab-made meat may lead you to conclude the dietary aspect of veganism is unnatural compared to sustenance derived from meat, milk, or eggs from a living being, just like our ancestors had. Even a diet consisting solely of whole plant foods—while not unheard of historically—can seem abnormal compared to how the human race has generally survived in the past.

The majority of humanity has been reliant on utilising animals in a variety of ways throughout history. So, when considering a life free from animal products, it's easy to lean with some satisfaction on the consideration that we are doing what people have always done. It's ordinary, instinctual, and natural... right?

While there was a time where the practice of animal agriculture was necessary, fortunately we are now alive in an age where much of the world is able to survive and thrive purely on a plant-based diet.

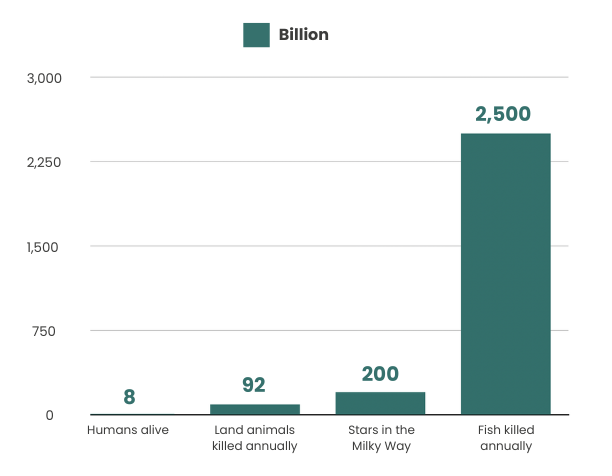

Yet, globally, over 92 billion land animals and between 2 and 3 trillion marine animals are slaughtered for food every single year.

That's 175,000 killed each passing minute; 3,000 a second. The number of land animals killed alone would fill 2,500 of the largest stadiums to capacity every single day, and each of those animals had a desire to live freely, a unique personality, and was capable of the same joy and sorrow as ourselves.

These numbers are incomprehensible. The scale and intensity have no historical, let alone natural, precedent; the small-scale subsistence hunting or farming of our ancestors bears little resemblance.

Modern farm animals themselves are markedly different from those of the past, being the product of intensive selective breeding. Broiler chickens grow four times faster than they did even in the 1950s; dairy cows produce around four times more milk than in the early 20th century.

These animals are genetically engineered for production efficiency, bringing a gamut of issues. Physiological problems for the animals are plentiful, including lameness, metabolic disorders, and oversized, painful udders.

Instead of grazing or foraging, most livestock are fed formulated feed (corn, soy, wheat byproducts, sometimes fishmeal), generally supplemented with synthetic vitamins and minerals we then consume when eating their flesh. This is a far cry from the natural grazing of the past, where those animals roamed freely, while today’s spend their lives indoors or in crowded feedlots.

Artificial (defined as “produced by human skill or labor, as opposed to occurring naturally”) insemination is the primary method of breeding. Lifespans are drastically shortened. A chicken's natural lifespan, for example, is up to 8–10 years, but we slaughter them at just 6–7 weeks. The cycles of reproduction and death are tightly engineered by humans rather than natural ecological processes.

Livestock now use about 80% of global agricultural land (ourworldindata.org), though they provide only 18% of global calories. These impacts are by-products of industrial systems, not natural ecological balances.

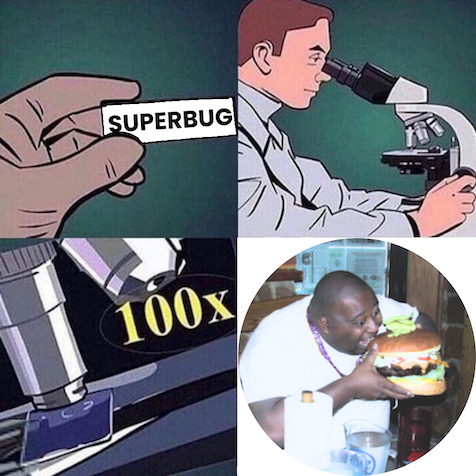

Widespread use of antibiotics in animal farming to promote growth and prevent disease in crowded conditions—linked to antimicrobial resistance in people—highlight how far these systems are from natural reproduction and health.

We have also lost our relationship with the animals we use. There was a more direct link between people and the animals who helped sustain them.

Now, the highly mechanised operation of factory farming means those trillions of individuals are treated solely as units of production. Most consumers never see the living animals hidden and suffering in our countrysides before their body parts make their way to our plates.

All of this, while important, barely needs saying. With honest looking, it is obvious that the animals we would treat with reverence and respect, as they helped us survive previously, are now instead a global commodity traded on stock markets.

So, yes, while humans have consumed animals for millions of years, modern animal agriculture is fundamentally, undeniably different. It is defined by scale and industrial efficiency rather than subsistence or natural cycles. And the subsequent issues that branch from treating sentient beings with truly unnatural barbarity are a ghastly and obvious consequence—though we have not yet seen the full ramifications.

Some may see the very few (around 1%) smaller, local farms, resembling more closely (but barely) the practices of the past, as preferable to factory farming. There is a reason these kinds of farms are the only ones we see in advertising. But they are not without their own problems; chiefly, we must still act in opposition to our instinctual compassion and kill fellow beings unnecessarily.

The sense that eating animals and their byproducts is more natural for people is a comforting blanket when considering the primary ethical dilemma of doing so.

But closer inspection proves this to be a comfort of little substance, woven from narratives that are far from the truth; these narratives, as ever, are craftily reinforced by the people who gain financially from the entirely unnatural use of living, feeling beings as a commodity barely worth our consideration.

What we see as ‘natural’ invariably shapes what we choose and are willing to accept. Those choices matter more than ever.

- H.R.