Veganism as Loss

"One who seeks knowledge learns something new every day.

One who seeks the Tao unlearns something new every day.

Less and less remains until you arrive at non‑doing."

- Lao Tzu, 'Tao Te Ching', Chapter 48

There are some who consider veganism to be a cult-like movement; one where you pledge allegiance to Earthling Ed, study the art of invasive preaching, receive a membership badge and, of course, protein deficiency.

But for us, turning away from animal products felt less like entering a cult and more like leaving one.

We lost something: specifically, a set of inherited beliefs and assumptions all stemming from a single root: that animals can, should, and must be treated as commodities.

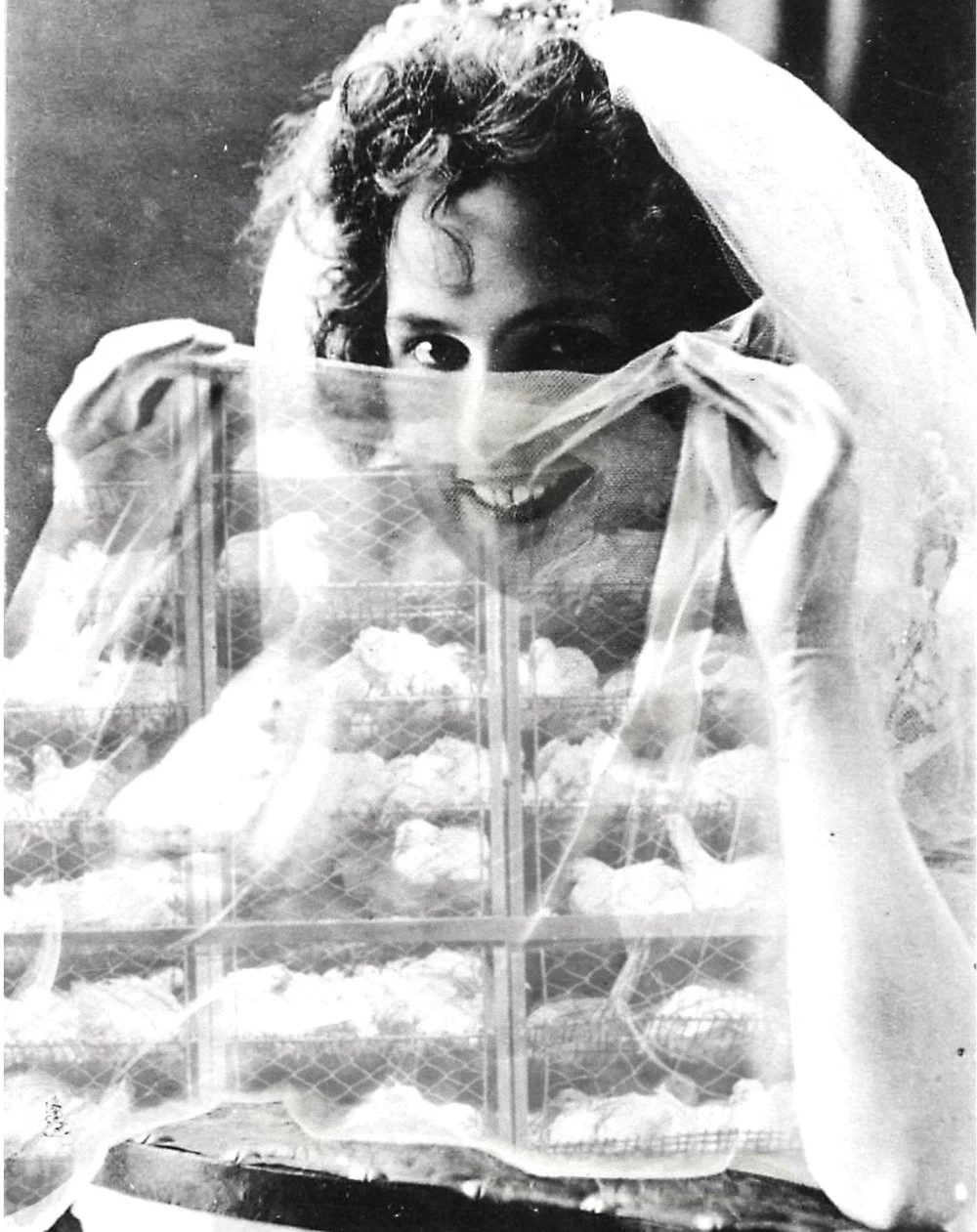

The combined beliefs that create this Megazord-like notion are a kind of veil which is woven with a mastery honed through millennia and slipped over most of us in childhood. This veil, maintained by those who stand to gain from its existence, distorts a base compassion; one which instinctually recognises in the eyes of an animal the same life and innocence within us, and when those eyes show suffering, we feel empathy and are compelled to assist.

This intuitive understanding is exemplified online, when a person filmed saving or helping an animal is lauded as a hero, while one harming an animal is branded a villain—often stirring up an otherwise unmatched indignation in most viewers.

The beliefs forming the veil that has us act in opposition to this understanding—like the one that separates the animal we see being harmed or saved on the internet from the one on our plate—are just that: beliefs. Yet together, they not only allow us to continue a way of life without confronting a potentially painful realisation, they become our reality.

They become not just beliefs, but truth. And for anyone to suggest otherwise would be to threaten a part of ourselves, because these beliefs are beams in the very foundations of our individual identities. When threatened, we will fearfully reinforce the beams most able to maintain the safety of the structure. We can accidentally build prisons out of supposed truths, however, so they are always worth examining with openness. We by no means see these words as an exception to this.

To illustrate the point, let’s imagine two people walk by a swan on a residential street.

One admires the bird as they pass. The swan carries on her day without injury, fear, or loss of life.

The other remembers their grandparents talking about how well swan meat pairs with a glass of sherry. They pay someone to wring her neck and prepare the carcass in such a way it barely resembles a bird at all. For the sake of a meal, the swan is caught, frightened, and killed.

As this person eats, an image of the carefree swan pops into their mind. They reassure themselves she lived a happy life, her death was probably painless, birds don’t feel emotions like people do—or even like pets. Humans are top of the food chain, aren't they? Doesn't that give them a right? Regardless, the swan’s dead now; why not enjoy the nutrients only meat provides?

Was the first person who passed by, acting on beliefs, or simply living in a manner that left the swan unharmed?

You could argue they did act on a belief: that animals deserve to exist without unnecessary, human-caused suffering and without any desire for sensory pleasure relying on their forced conception, existence, and death. We won't deny that's a belief. Of course it is! Beliefs are sewn into the fabric of our being.

But it's likely that letting the swan be was a natural, unconsidered response. When compared to the second person’s justifications, carrying maximum consequences from the swan's perspective, person one resonates more with the child in us; the child who regards any animal, swan or otherwise, as a valued equal and could not conceive of exploiting them.

Their approach, or lack thereof, feels lighter than the bundle of beliefs we ourselves wore, consciously or otherwise, when we sat down to a meal. We gladly sported the veil that dulled the discomfort of acting against our admiration for animals and against our natural inclination to do good by other beings capable of the same joys, sorrows, and desire to live as ourselves.

Yes, veganism is a label and a useful one, and we won't deny some may weave new veils after adopting it.

But it’s not much of a stretch to consider a shift in perspective: what if doing our best to avoid harming other sentient beings where possible didn’t need a label? What if, in a world where animal suffering is generally, rightfully abhorred, and their exploitation is no longer a necessity, that was simply the baseline?

Maybe, like other belief-bound traditions we’ve outgrown, it’s the ones allowing harm—those justifying violence, dulling empathy, or comforting us with illusions for fleeting pleasure—that deserve to be labelled, and one day, left in the past.

- H.R